Increasing Tobacco Prices Through Non-Tax Approaches

According to the Surgeon General, raising the price of tobacco products is one of the most effective strategies for reducing initiation, decreasing consumption, and increasing cessation. It also has a pro-equity effect on smoking.[1] While raising excise taxes is the gold standard for raising the price of tobacco products, other non-tax opportunities exist for states and communities facing political barriers to excise tax increases.

These strategies include the following (click on each to scroll down for more information):

- Implementing or strengthening minimum price laws;

- Banning price discounting/multipack offers;

- Increasing tobacco retail licensing fees;

- Instituting mitigation fees; and

- Implementing disclosure or sunshine laws for payments or discounts to retailers.

The first two of these strategies also have the benefit of counteracting industry attempts to subvert tax increases through price discounts paid to retailers or wholesalers, which, according to the Federal Trade Commission, accounted for nearly 86% of the industry’s advertising and promotional expenditures for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco in 2022.

For a primer, review:

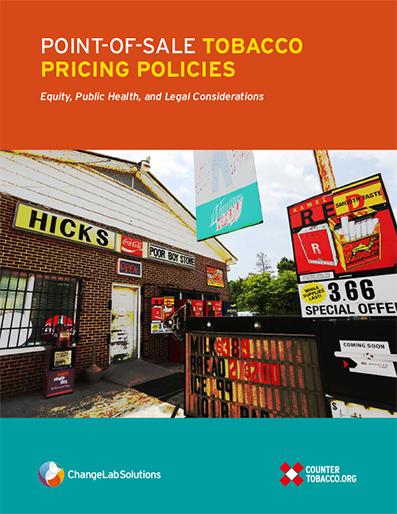

In partnership with ChangeLab Solutions, we created this new fact sheet and infographic for local and state tobacco control advocates who are looking to enact point-of-sale (POS) tobacco pricing policies and improve community health and equity. The POS pricing approaches covered in these resources include:

In partnership with ChangeLab Solutions, we created this new fact sheet and infographic for local and state tobacco control advocates who are looking to enact point-of-sale (POS) tobacco pricing policies and improve community health and equity. The POS pricing approaches covered in these resources include:

- Minimum floor price laws for all tobacco products

- Minimum pack sizes for little cigars and cigarillos

- Prohibiting coupons, price discounts, and promotions

- Public Health Law Center’s “Death on a Discount: Regulating Tobacco Product Pricing“

- Public Health Law Center’s Webinar “The Cost of Access: Raising the Price of Tobacco Products“

- Public Health Law Center’s “Price-Related Promotions for Tobacco Products: An Introduction to Key Terms & Concepts”

- California Department of Public Health’s “Tobacco Retail Price Manipulation Policy Strategy Summit Proceedings”

- Public Health and Tobacco Policy Center’s“Tobacco Price Promotion: Policy Responses to Industry Price Promotion”

- Public Health and Tobacco Policy Center’s “Tobacco Product Pricing Policy in Vermont“

Review best practices for getting started below.

What are Minimum Price Laws?

A strong Cigarette Minimum Price Law (CMPL) at the state level sets a floor price for cigarettes, or a price below which cigarettes cannot be sold. According to a MMWR study, as of December 31, 2009, 25 states (including Washington, DC) had CMPLs. There are several options for crafting CMPLs:

- Establish minimum markups when cigarettes are sold from wholesalers to retailers or from retailers to consumers, with a separate minimum price for every brand because wholesaler and retailer costs vary by brand. While this is the most common approach, most current CMPLs contain loopholes that limit their effectiveness. [2]

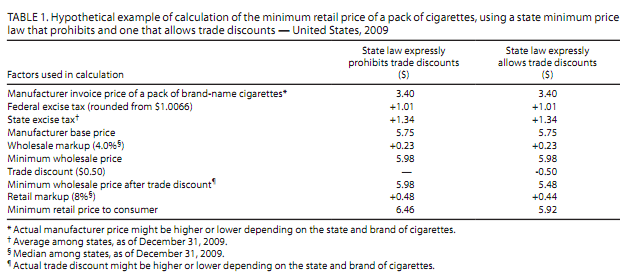

- Strengthen CMPLs by excluding trade discounts (eliminating one of the loopholes mentioned above, which the tobacco industry lobbied for[16]) from the calculation of minimum price, which seven states have done. See the table below for an example comparison of the calculation of the minimum retail price of a pack of cigarettes with a minimum price law that expressly prohibits and one that expressly allows trade discounts.

- Establish a floor price (e.g., $5.00 per pack) below which no pack could be sold, regardless of the wholesale price. This approach was implemented in New York City. The flat-rate minimum price would need to be pegged to inflation or increased every few years to account for inflation. Learn more about minimum floor price laws.

- Establish a hybrid law that establishes a minimum price law that also requires substantial minimum percentage markup for all products and bans price discount tactics. [3]

Source: CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report State Cigarette Minimum Price Laws – United States, 2009 (Ribisl, K.M., et al., 2009).

- Implement a minimum price law with a minimum pack size for cigars and cigarillos (little cigars): While cigarettes must come in packs of 20 or more, there are no federal regulations on pack sizes for cigars and cigarillos. This allows companies to sell the products at extremely low prices making them appealing to price sensitive shoppers like youth. However, localities can also establish floor prices for other tobacco products, and pairing a floor price with a minimum pack size requirement can further strengthen the law. For example, New York City’s law requires a minimum price of $3.00 for any single cigar sold. Otherwise, little cigars must be sold in packs of at least 20 and cost at least $13, the same as cigarettes. In 2012, Boston implemented a cigar packaging and pricing regulation that set a minimum price for single cigars at $2.50 each and required all other cigars to be sold in packs of 4 or more.[4] The ordinance language was later updated to require a package of two cigars to cost more than $5.00, and a package of three cigars to cost more than $7.50 and similar policies have since been adopted in at least 173 municipalities in Massachusetts.[4] Several Minnesota cities have implemented similar policies. For more information, review the following resources:

- Changelab Solutions’ “Limiting ‘Teen Friendly’ Cigars: What Communities Can Do” and Minimum Pack Size for Cigars Model Ordinance

- Public Health Law Center’s “Regulating Tobacco Products Based on Pack Size- Tips and Tools”

For more information on Minimum Price Laws (MPLs), review the following resources:

- ChangeLab Solution’s

- UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health’s Factsheet “Minimum Floor Price Laws”

- Public Health Law Center’s

- MMWR Study: “State Cigarette Minimum Price Laws — United States, 2009”

- Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids’ Regulating Package Size and Setting a Minimum Price Will Help Reduce Cigar Use Among Kids: Responses to Misleading NATO/Swedish Match Arguments

The evidence for implementing or strengthening tobacco minimum price laws

By using trade discounts and buy-downs, the tobacco industry is often able to keep cigarette prices low even in the face of excise tax increases. A strong minimum price law can prevent this type of price manipulation. A study using data from 2007-2014 found that states with minimum price laws had 5–11% higher prices for low-priced cigarettes and 3–9% higher median cigarette prices.,[5] In addition, states whose laws prohibited multi-pack discounts that dropped the price below the minimum, the distribution of below-cost coupons, trade discounts that reduce the base cost, and competitor price matching had prices had were higher than in state without these components.[5] States with minimum markup rates greater than 24% also had higher cigarette prices that were 53 cents (12%) higher.[5] Strong minimum price laws can also prevent price manipulation by geographic area or by brand, thereby reducing targeting of products to certain populations, such as low income and racial and ethnic minority populations as well as youth, who are particularly price sensitive. A national study with a representative sample of tobacco retailers across the US found that while the average price for a pack of cigarettes in 2015 was $5.17, prices were $0.04 cheaper for every standard deviation increase in the percentage of youth living in the neighborhood, and $0.22 cheaper in neighborhoods with the lowest median household income than in neighborhoods with the highest median household income.[6] A modeling study predicts that establishing a national minimum price of $10 per pack of cigarettes would reduce cigarette sales in the United States by 5.7 billion packs per year and could result in 10 million smokers quitting.[7]

Establishing minimum prices for all tobacco products may help encourage price sensitive users to quit rather than switch to a lower-cost product.[8] For example, in many places little cigars and cigarillos are sold for less than a dollar. One study found that a 10% increase in cigarette price led to a 27% increase in little cigar sales, but increasing little cigar prices by 10% led to a 32% decrease in little cigar sales.[8]

In Oakland, CA, implemented a minimum floor price law for cigarettes and cigars at $8 or per pack, and 20 months later, cigarettes that had previously been sold below the minimum increased in price by 8% and decreased in average monthly sales by 25.2% and researchers found no evidence that people were instead buying higher-priced cigarettes, cigars, e-cigarettes, or NRT. [12]

Minimum price laws for cigars may result in a reduction of retail availability in addition to an increase in price and may reduce youth access to and use of cigars. Following implementation of a minimum pricing policy for cigars in three Minnesota cities, the price for single cigars and 2-or 3-packs increased significantly, and percentage of retailers selling single cigars decreased from 80% to 45%.[9] Similar results were seen for flavored cigar sales following Boston’s implementation of cigar minimum price policy, with the price for single grape-flavored Dutch Masters cigars (which are popular with youth) increasing by $1 and the percentage of Boston retailers selling grape-flavored DM single cigars decreasing by 34.5%.[10] Additionally, the number of neighborhoods with 3 or more retailers selling these cigars per 100 youth residents decreased from 12 stores to 3, reducing neighborhood-level disparities in retail availability.[10] Widespread adoption of this type of policy can also impact prices and availability in places without the policy in place. Between 2012 and 2018, 151 municipalities across Massachusetts enacted minimum pricing policies for single and 2-packs of cigars, and subsequently the average price of a single cigar across the state rose from $1.35 in 2014 to $1.64 in 2018, and availability of single cigars decreased from 49% of stores to 21%.[11] While prices were higher and availability lower in localities with the policy in place, localities without the policy were also affected.[11] In addition, Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey data indicated that use of cigars among high schoolers across the state dropped from 14.3% in 2011 to 6.7% in 2017.[11]

In 2013, New York City passed a comprehensive point of sale policy, Sensible Tobacco Enforcement, which restricted price discounts by prohibiting retailers from redeeming coupons or honoring other price discounts for tobacco products, set a minimum price for cigarettes and little cigars at $10.50 per pack, set minimum packaging requirements, and increased enforcement and penalties for tax evasion. At the same time, the city also passed legislation that raised the minimum age to purchase tobacco and e-cigarettes from 18 to 21. Learn more about NYC’s point of sale policy success, the policies’ impacts on public health, legal considerations, and lessons learned in Reducing Cheap Tobacco & Youth Access: New York City, a case study in the Innovative Point-of-Sale Policies series from the Center for Public Health Systems Science at Washington University in St. Louis.

In November 2021, St. Paul, MN passed a set of retail tobacco policies that will help improve health equity, reduce youth tobacco use, and reduce the presence of tobacco across communities in the city. These included minimum floor prices for both cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products, a ban on price discounts and coupon redemption for all tobacco products, tobacco retailer density limits, and more. We had the privilege of talking with two representatives from the Association for Nonsmokers-Minnesota (ANSR-MN), an organization that helped lead the organizing and advocacy efforts that brought these policies to fruition, including community organizing efforts and a fantastic media campaign called “Don’t Discount My Life.” Learn more in Point-of-Sale Pricing Policies in St. Paul: A Story from the Field.

In November 2021, St. Paul, MN passed a set of retail tobacco policies that will help improve health equity, reduce youth tobacco use, and reduce the presence of tobacco across communities in the city. These included minimum floor prices for both cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products, a ban on price discounts and coupon redemption for all tobacco products, tobacco retailer density limits, and more. We had the privilege of talking with two representatives from the Association for Nonsmokers-Minnesota (ANSR-MN), an organization that helped lead the organizing and advocacy efforts that brought these policies to fruition, including community organizing efforts and a fantastic media campaign called “Don’t Discount My Life.” Learn more in Point-of-Sale Pricing Policies in St. Paul: A Story from the Field.

What are price discount and multipack offer bans?

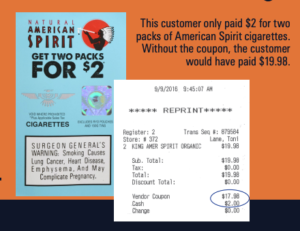

According to the Federal Trade Commission, price promotions accounted for nearly 86% of the industry’s advertising and promotional expenditures in 2022. These include price discounts of $.50 or $1.00/per pack (aka “buydowns”), or offer bonus cigarettes with purchase such as buy two get one free (aka “retail value added”). Read more about different types of industry price promotions. Bans on price discounts include the following approaches:

According to the Federal Trade Commission, price promotions accounted for nearly 86% of the industry’s advertising and promotional expenditures in 2022. These include price discounts of $.50 or $1.00/per pack (aka “buydowns”), or offer bonus cigarettes with purchase such as buy two get one free (aka “retail value added”). Read more about different types of industry price promotions. Bans on price discounts include the following approaches:

- Restricting coupon redemption, multi-pack discounts, and “buy one get one offers” as standalone laws or as part of tobacco retailer licensing agreements. Providence, RI was the first to ban coupon redemption and multi-pack discounts in 2012 and New York City proposed a similar ban in March 2013. This type of policy has withstood both preemption and First Amendment challenges in court. [11] For example, states and localities can include these restrictions as part of tobacco retailer licensing agreements. Three states (New York, New Jersey, and Rhode Island) have now passed policies that prohibit price discounts and/or coupon redemption for tobacco products. For more information, visit

- CounterTobacco.Org’s page on licensing and zoning

- Public Health Law Center’s “Tobacco Coupon Regulations and Sampling Restrictions—Tips and Tools” and sample language for prohibiting coupon redemption in tobacco licensing ordinances.

- Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids’ Regulating Package Size and Setting a Minimum Price Will Help Reduce Cigar Use Among Kids: Responses to Misleading NATO/Swedish Match Arguments

- Restricting tobacco sampling. The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act restricted most tobacco sampling, but it is still allowed in certain settings. For more information, review:

- Public Health Law Center’s “Tobacco Coupon Regulations and Sampling Restrictions—Tips and Tools” to learn about strategies for closing loopholes in the Tobacco Control Act.

- ChangeLab Solutions’ Model Tobacco Sampling Ordinance.

In 2012 Providence R.I. became the first municipality in the U.S. to prohibit tobacco retailers from selling tobacco products at a discount, through multi-pack or buy-some-get-some-free deals, and redeeming coupons that provide tobacco products for free or at a reduced price. These policy successes were the result of a multi-year campaign that included passing a successful licensing policy, conducting store assessments and public opinion surveys, the development and promotion of the Sweet Deceit media campaign, and building community and political support around the issue. After being challenged in court by the tobacco industry, the provisions were upheld by the First Circuit Court of Appeals and went into effect in 2013.

In 2012 Providence R.I. became the first municipality in the U.S. to prohibit tobacco retailers from selling tobacco products at a discount, through multi-pack or buy-some-get-some-free deals, and redeeming coupons that provide tobacco products for free or at a reduced price. These policy successes were the result of a multi-year campaign that included passing a successful licensing policy, conducting store assessments and public opinion surveys, the development and promotion of the Sweet Deceit media campaign, and building community and political support around the issue. After being challenged in court by the tobacco industry, the provisions were upheld by the First Circuit Court of Appeals and went into effect in 2013.

Learn more about Providence’s tobacco pricing policy success in Regulating Price Discounting in Providence, R.I., a case study in the Innovative Point-of-Sale Policies series from the Center for Public Health Systems Science at Washington University in St. Louis.

New York City’s Sensible Tobacco Enforcement banned price discounts by prohibiting retailers from redeeming coupons or honoring other price discounts for tobacco products, set a minimum price for cigarettes and little cigars at $10.50 per pack, set minimum pack size of 20 for little cigars and cigarillos, and increased enforcement and penalties for tax evasion. Read more.

Case Study: Reducing Cheap Tobacco & Youth Access: New York City. Learn more about NYC’s point of sale policy success, the policies’ impacts on public health, legal considerations, and lessons learned.

The evidence for implementing price discount and multipack offer bans

Price discounts are the largest single category of tobacco industry spending on advertising and promotions and are used to counteract the impact of increased excise taxes or to target price sensitive smokers. In 2012, 30% of youth reported recent exposure to coupons for tobacco, and exposure was associated with greater intentions to purchase cigarettes, higher susceptibility to smoking among never smokers and lower confidence in quitting among current smokers.[12] A study examining cigarette prices following California’s 2017 $2.00 cigarette tax increase found an increase in price discounts after the tax was implemented. [13] In addition, the cost of the tax increase was not passed through to consumers equally, with prices for Newport cigarettes in neighborhoods with more African-American residents and prices for Pall Malls in neighborhoods with more Hispanic residents increasing less than the tax amount. [13] Combining minimum price laws with a ban on discounting is a particularly strong policy approach. According to the Surgeon General, raising the price of tobacco products (e.g., through POS price promotion restrictions) is one of the most effective strategies to reduce tobacco consumption, decrease initiation, and increase cessation. Particularly when combined with minimum price laws and excise taxes, prohibiting tobacco industry price reduction practices, such as prohibiting price promotions, multipack promotions and coupons, is key to creating a strong tobacco minimum price law. [14]

An international study found that in countries that allow price promotions (e.g. the United States and Australia), participants who were frequently exposed to tobacco price promotions were more likely to believe smoking has functional value (e.g. can calm someone down) and were more likely to smoke two years later.[15]

Learn more about pricing strategies in ‘Pricing Policy: a Tobacco Control Guide‘ from CPHSS and the Public Health Law Center.

Gather more evidence on how Prohibiting Price Promotions and Coupon Redemptions Benefit Public Health: Responses to Misleading NATO/Swedish Match Arguments.

What are retailer licensing fees?

An increase in tobacco retailer licensing (TRL) fees can be considered when implementing or strengthening a state or local licensing law (see CounterTobacco.Org’s Licensing & Zoning page). Best practices show that fees should be tied to demonstrable costs related to tobacco sales (e.g., comprehensive enforcement, costs of administering a tobacco control program, health care costs or the cost of providing education). Public Health Law Center’s “TRL Calculator” provides guidance on projecting enforcement costs and determining appropriate licensure fees for your area.

The evidence for implementing retailer licensing fees

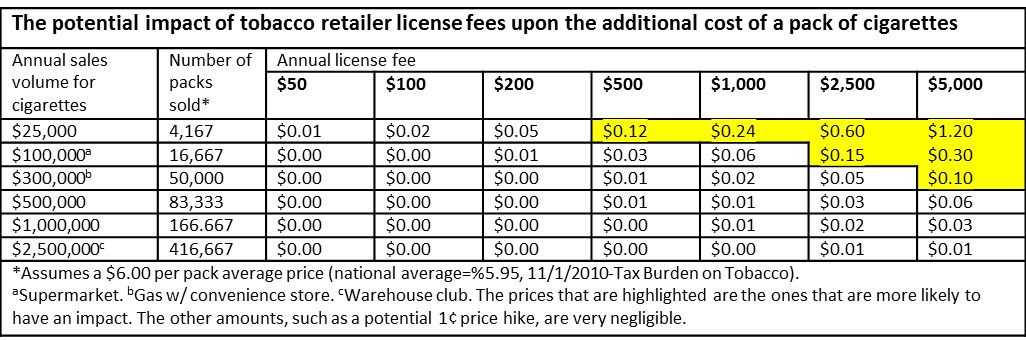

Most existing TRL fees are too low to require retailers with large sale volumes to pass on any costs to the consumer. However, there is potential for sizeable increases in licensing fees to impact retail pack prices. See the table below for an assessment of the potential impact of tobacco retailer license fees on the additional cost of a pack of cigarettes. The two prior strategies are more likely to lead to notable increases in tobacco prices. However, new research indicates that raising tobacco retail licensing fees may also have the added benefit of reducing the number of tobacco retailers. [3]

What are mitigation fees?

A mitigation fee for cigarettes is an added fee on each pack of cigarettes sold to cover costs the government incurs related to improperly discarded cigarette butts. The fee might be used to offset the cost of litter collection and disposal, public education, signage, and administration of the fee program. The needs to be used to cover the intended purpose and cannot be used to raise general revenue. For more information, review:

- Public Health Law Center’s Tobacco Product Waste: A Public Health and Environmental Toolkit

- San Francisco’s Cigarette Litter Abatement Fee

San Francisco adopted a Cigarette Litter Abatement Fee at the rate of 20 cents per pack of cigarettes. Since then, the fee has increased to 85 cents per pack. According to a 2009 report from the Health Economics Consulting Group, the city of San Francisco spent over 6 million dollars in 2008 removing cigarettes from gutters, drainpipes and sidewalks. San Francisco has also proposed a fast food litter fee. No studies have assessed the effectiveness of this approach on raising prices, but presumably the impact would be akin to an excise tax. For more information, see the text of the San Francisco Ordinance of Cigarette Litter Abatement Fee.

Another option is to shift the burden of responsibility and cost for tobacco waste cleanup to the consumer and the producer through Extended Producer Responsibility. Learn more in Tobacco industry responsibility for butts: A Model Tobacco Waste Act, a special communication in the journal Tobacco Control and download the Model Tobacco Waste Act.

The evidence for implementing mitigation fees

Cigarette butts constitute the most common type of litter and contain toxins like ammonia, formaldehyde, benzene, and butane.[9] In addition to the impact associated with raising the price of cigarettes, mitigation fees therefore have the duel benefit of funding programs that benefit the environment.

What are sunshine laws?

A sunshine law would require public disclosure of price discounting and promotional allowance payments. A variation might be to amend a state or local tobacco retailer licensing program to require retailers to disclose how much money they receive from manufacturers for price promotions. For more information, review Public Health Law Center’s “Sunshine Laws: Requiring Reporting of Tobacco Industry Price Discounting and Promotional Allowance Payments to Retailers and Wholesalers—Tips and Tools.” To our knowledge, no jurisdiction has implemented this type of sunshine law.

The evidence for implementing a sunshine law

A sunshine law could help bring attention to the disparate discounting which may stigmatize and discourage these payments to retailers, thereby increasing prices. Read more on disparities in pricing . While the Federal Trade Commission aggregates these data nationally, a sunshine policy could mandate disclosure at the city or state level or by manufacturer, as well as provide information that is more up-to-date. Sunshine laws can also facilitate enforcement of compliance with the Master Settlement Agreement and state CMPLs.

Best Practices for Getting Started

- Review the “Assessing Alternative Tobacco Price Policy Options” document

- Check to see if your state or locality has existing cigarette minimum price laws, tobacco retail licensing laws, mitigation fees, or sunshine laws and if they need to be strengthened.

- Find out if your state preempts local regulation of tobacco. Preemption means that the laws at a higher level of government take precedence over the laws at a lower level of government. For more information on preemption, review the following resources:

- Consult legal experts. The information on this site and associated resources are no substitute for actual legal advice. It’s important to prepare for potential legal challenges by the tobacco industry, such as the following:

- The tobacco industry may argue that efforts to restrict price promotions violate First Amendment Commercial Speech protections or the Commerce Clause. Review the following resources from the Public Health Law Center and the Center for Public Health & Tobacco Policy for more details:

- The tobacco industry may argue that a sunshine law constitutes release of trade secrets. Review the Public Health Law Center’s “Tobacco Control and the Takings Clause—Tips and Tools” for more information.

- Meet with designated enforcement agencies.

- Monitor compliance with new or existing policies

- Conduct store audits (such as a Walking Tobacco Audit, Operation Storefront, or STARS) and publicize results. Documenting industry price promotions in your community can be a powerful way to draw attention to the problem and garner support. You can also share images of tobacco advertising and promotions in your community or view images from other communities through Counter Tobacco’s image gallery.

- Conduct public opinion surveys to gauge public support for a proposed policy.

- Engage stakeholders. Review the CDC’s Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs for tips.

- Meet with designated enforcement agencies. Understanding existing enforcement mechanisms, enlisting the support of enforcement agencies and including provisions for strong enforcement is important to policy implementation.

- Include strong penalties in any proposed policy and monitor compliance with any new or existing laws.

Special thanks to Kurt M. Ribisl, Todd Rogers and Maggie Mahoney, developers of Assessing Alternative Tobacco Price Policy Options, a handout presented at a Communities Putting Prevention to Work (CPPW) Annual Training on March 29, 2011. Their work heavily informs this section of CounterTobacco.org.